Human Development Report 1999

TEN YEARS OF HUMAN DEVELOPMENT

When I was arguing that helping a

one-meal family

to become a two-meal family, enabling a woman

without a change of clothing

to afford to buy a second piece of clothing, is a

development miracle,

I was ridiculed. That is no development, I was

reminded sternly.

Development is growth of the economy, they said;

growth will bring everything.

We carried out our work as if we were engaged in

some very undesirable activities.

When UNDP’s Human Development Report came out

we felt vindicated.

We were no longer back-street operators, we felt we

were in the mainstream.

Thanks, Human Development Report.

PROFESSOR MUHAMMAD YUNUS, FOUNDER, GRAMEEN BANK,

BANGLADESH

________________________________________________________________

In 1990 the time had come for a broad approach to improving human well-being that would

cover all aspects of human life, for all people, in both high-income and developing

countries, both now and in the future. It went far beyond narrowly defined economic

development to cover the full flourishing of all human choices. It emphasized the need to

put people—their needs, their aspirations and their capabilities—at the center

of the development effort. And the need to assert the unacceptability of any biases or

discrimination, whether by class, gender, race, nationality, religion, community or

generation. Human development had arrived.

The first Human Development Report of UNDP,

published in 1990 under the inspiration and leadership of its architect, Mahbub ul Haq,

came after a period of crisis and retrenchment, in which concern for people had given way

to concern for balancing budgets and payments. It met a felt need and was widely welcomed.

Since then it has caused considerable academic discussion in journals and seminars. It has

caught the world's imagination, stimulating criticisms and debate, ingenious elaborations,

improvements

and additions.

Human development is the process of enlarging

people's choices—not just choices among different detergents, television channels or

car models but the choices that are created by expanding human capabilities and

functionings—what people do and can do in their lives. At all levels of development a

few capabilities are essential for human development, without which many choices in life

would not be available. These capabilities are to lead long and healthy lives, to be

knowledgeable and to have access to the resources needed for a decent standard of

living—and these are reflected in the human development index. But many additional

choices are valued by people. These include political, social, economic and

cultural freedom, a sense of community, opportunities for being creative and productive,

and self-respect and human rights. Yet human development is more than just achieving these

capabilities; it is also the process of pursuing them in a way that is equitable,

participatory, productive and sustainable.

Choices will change over time and can, in

principle, be infinite. Yet infinite choices without limits and constraints can become

pointless and mindless. Choices have to be combined with allegiances, rights with duties,

options with bonds, liberties with ligatures. Today we see a reaction against the extreme

individualism of the free market approach towards what has come to be called

communitarianism. The exact combination of individual and public action, of personal

agency and social institutions, will vary from time to time and from problem to problem.

Institutional arrangements will be more important for achieving environmental

sustainability, personal agency more important when it comes to the choice of household

articles or marriage partners. But some complementarity will always be necessary.

Getting income is one of the options people

would like to have. It is important but not an all-important option. Human development

includes the expansion of income and wealth, but it includes many other valued and

valuable things as well.

For example, in investigating the priorities of

poor people, one discovers that what matters most to them often differs from what

outsiders assume. More income is only one of the things poor people desire. Adequate

nutrition, safe water at hand, better medical services, more and better schooling for

their children, cheap transport, adequate shelter, continuing employment and secure

livelihoods and productive, remunerating, satisfying jobs do not show up in higher income

per head, at least not for some time.

There are other non-material benefits that are

often more highly valued by poor people than material improvements. Some of these partake

in the characteristics of rights, others in those of states of mind. Among these are good

and safe working conditions, freedom to choose jobs and livelihoods, freedom of movement

and speech, liberation from oppression, violence and exploitation, security from

persecution and arbitrary arrest, a satisfying family life, the assertion of cultural and

religious values, adequate leisure time and satisfying forms of its use, a sense of

purpose in life and work, the opportunity to join and actively

participate in the activities of civil society and a sense of belonging to a community.

These are often more highly valued than income, both in their own right and as a means to

satisfying and productive work. They do not show up in higher income figures. No

policy-maker can guarantee the achievement of all, or even the majority, of these

aspirations, but policies can create the opportunities for their fulfilment.

PAUL STREETEN

_________________________________________________________________________

Human Development Reports have had a significant impact worldwide.

Up until the publication of these Reports, discussions on development centred on

economic growth, using variables such as per capita income growth. Of course these

economic variables also generate some social benefits. But this view of development had

been quite limited. While a country could perfectly well be considered highly developed,

income might be concentrated in the hands of a few, and poverty worsening…. Speaking

as President of Brazil, until today the country is plagued by a lot of

problems—income concentration, poverty, and so on. If we do not adopt a

development model that responds to the needs of the majority, this development will not be

long-lasting. FERNANDO HENRIQUE CARDOSO, PRESIDENT, BRAZIL

__________________________________________________________________________

This year’s Report marks the tenth anniversary of the Human Development Report.

Each year since being launched in 1990, the Report has focused on different themes and

introduced new concepts and approaches. But the central concern has always been people as

the purpose of development, and their empowerment as participants in the development

process. The Report puts economic growth into perspective: it is a means—a very

important one—to serve human ends, but it is not an end in itself.

ACCOUNTING FOR THE FIRST 10 YEARS

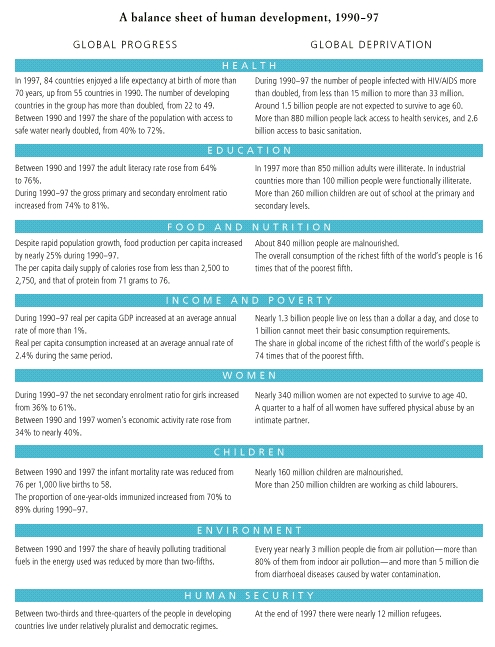

How has human development changed since the Report was first published in 1990? A

balance sheet of human development in 1990–97 shows tremendous progress—but also

enduring deprivations and new setbacks.

POLICY PROPOSALS OVER THE YEARS

Each year the Human Development Report has made strong policy recommendations, for both

national and international action. The proposals, some emphasizing suggestions by others,

some putting forward new approaches, have drawn both criticism and praise. But most

important, they have helped to open policy debates to wider possibilities.

GLOBAL PROPOSALS

Global proposals have been aimed at contributing to a new paradigm of sustainable human

development—based on a new concept of human security, a new partnership of developed

and developing countries, new forms of international cooperation and a new global compact.

THE 20:20 INITIATIVE (1992). With

the aim of turning both domestic and external priorities to basic human concerns, this

initiative proposed that every developing country allocate 20% of its domestic budget, and

every donor 20% of its official development assistance (ODA), to ensuring basic health

care, basic education, access to safe water and basic sanitation, and basic family

planning packages for all couples.

GLOBAL HUMAN SECURITY FUND (1994). This

fund would tackle drug trafficking, international terrorism, communicable diseases,

nuclear proliferation, natural disasters, ethnic conflicts, excessive international

migration and global environmental pollution and degradation. The fund of $250 billion a

year would be financed with $14 billion from a proportion of the peace dividend (20% of

the amount saved by industrial countries and 10% of that saved by developing countries

through a 3% reduction in global military spending); $150 billion from a 0.05% tax on

speculative international capital movements; $66 billion from a global energy tax ($1 per

barrel of oil or its equivalent in coal consumption) and $20 billion from a one-third

share of ODA.

A NEW GLOBAL ARCHITECTURE (1994). A

globalizing world needs new institutions to deal with problems that nations alone cannot

solve:

- An economic security council—to review the threats to human security.

- A world central bank—to take on global macroeconomic management and supervision of

international banking.

- An international investment trust—to recycle international surpluses to developing

countries.

- A world antimonopoly authority—to monitor the activities of multinational

corporations and ensure that markets are competitive.

A TIMETABLE TO ELIMINATE LEGAL GENDER

DISCRIMINATION (1995). As of December 1998, 163 countries had ratified the 1979

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), but

others—including the United States—had not. Women's rights are human rights.

There should be a timetable for recognizing legal equality between women and men

everywhere, say by 2005, using CEDAW as the framework.

_________________________________________________________________________ The

issues raised by this Report [Human Development Report 1995] are of central importance to

all of us…. In country after country women have demonstrated that when given the

tools of opportunity—education, healthcare, access to credit, political participation

and legal rights—they can lift themselves out of poverty, and as women realize their

potential, they lift their families, communities and nations as well…. This Report

not only provides a graphic portrait of the problems facing today’s women, but also

opens up the opportunity for a serious dialogue about possible solutions. It challenges

governments, communities and individuals to enter

into this conversation in a common effort to overcome shared problems.

HILLARY RODHAM CLINTON, FIRST LADY, THE UNITED STATES

__________________________________________________________________________

NATIONAL PROPOSALS

National proposals have focused on the centrality of people in development, on the need

for a new partnership between the state and the market and on new forms of alliance

between governments, institutions of civil society, communities and people.

RESTRUCTURING SOCIAL EXPENDITURES (1991).

Resources should be reallocated to basic human priority concerns through an analysis of a

country’s total expenditure, social expenditure and human priority spending ratios.

The key is to move away from military spending towards social spending—and to shift

the focus to primary human concerns: better education, health services and safe water

accessible to poor people.

A CRITICAL THRESHOLD OF 30% FOR WOMEN’S

REPRESENTATION (1995). Women must have a critical 30% representation in all

decision-making processes—economic, political and social—nationally and locally.

Reaching this threshold is essential to enable women to influence decisions that affect

their lives. And to achieve gender equality, social norms and practices must be changed,

and women’s access to social services, productive resources and all other

opportunities made equal to men’s.

PRO-POOR GROWTH (1996). The quality of

economic growth is as important as its quantity. For human development, growth should be

job-creating rather than jobless, poverty-reducing rather than ruthless, participatory

rather than voiceless, culturally entrenched rather than rootless and environment-friendly

rather than futureless. A growth strategy that aims for a more equitable distribution of

assets, that is job-creating and labour-intensive, and that is decentralized can achieve

such growth.

AGENDA FOR POVERTY ERADICATION (1997).

People’s empowerment is the key to poverty elimination and at the centre of a

six-point agenda:

- Empower individuals, households and communities to gain greater control over their lives

and resources.

- Strengthen gender equality to empower women.

- Accelerate pro-poor growth in low-income countries.

- Improve the management of globalization.

- Ensure an active state committed to eradicating poverty.

- Take special actions for special situations to support progress in the poorest and

weakest countries.

_________________________________________________________________________

The Human Development Report has become an important instrument of policy

and the concept of the human development index a fundamental tool in formulation of

policy by government…. Growth and advancement must be measured by the extent to which

it impacts positively on people, but the starting point must be human development. We need

to focus particularly on the sectors of society that are the most disadvantaged—

women, youth, children, the elderly and the disabled. THABO

MBEKI, DEPUTY PRESIDENT, SOUTH AFRICA

__________________________________________________________________________

HUMAN DEVELOPMENT AS A NATIONAL TOOL

The human development approach has tremendous potential for analysing situations and

policies at the national level. Two Human Development Centres have been

established—the first in Islamabad, Pakistan, and the second in Guanajuanto, Mexico.

More than 260 national and subnational human development reports have been produced over

the years by 120 countries, in addition to nine regional reports. In each country these

serve to bring together the facts, influence national policy and mobilize action. They

have introduced the human development concept into national policy dialogue—not only

through human development indicators and policy recommendations, but also through the

country-led process of consultation, data collection and report writing.

SOUTH AFRICA—UNDERSTANDING THE FULL COSTS OF

HIV/AIDS

South Africa has one of the fastest-spreading HIV epidemics in the world. The

country’s 1998 human development report provided startling information on how this

will affect human development. Many of the advances achieved during the short life of the

new democracy will be reversed if the epidemic goes unchecked. Developing and drafting the

report brought critical gaps in information to light. The economic costs alone, in lost

labour and sick days, are far greater than initially realized. The report has prompted

plans for further study of the full costs—direct and indirect—of the epidemic to

the government, to communities and to households.

INDIA—STATE REPORTS INFLUENCING POLICY

Many of India’s 25 states rival medium-size countries in size, population and

diversity. National-level aggregation would hide these important regional disparities.

UNDP India has therefore supported the preparation of human development reports by state

governments. The government of Madhya Pradesh was the first to prepare a state report, in

1995, which helped bring human development into political discourse and planning. Its

second report, in 1998, reflects the influence the first report had on planning. Social

services now account for more than 42% of plan investment, compared with 19% in the

previous plan budget. This success bodes well for other states, such as Gujarat, Karnataka

and Rajasthan, preparing their first human development reports in 1999.

KUWAIT—INTRODUCING THE HUMAN DEVELOPMENT

PERSPECTIVE

Kuwait’s first human development report, in 1997, raised awareness of the human

development concept and its relevance to the country’s struggle to shift from

dependence on oil towards a knowledge-based economy. The report’s production and

promotion helped advance new thinking in academia, research institutions and the

government. The Ministry of Planning has started to incorporate the human development

approach in its indicators for strategic planning and to monitor human development. The

Arab Planning Institute has revised its curriculum to reflect the human development

concept. And after the success of the first report, the Ministry of Planning is following

up with a second, fully funded by the government.

GUATEMALA—ALERTING THE COUNTRY TO THE NEED FOR

DATA

Guatemala’s first human development report, in 1998, overcame data limitations to

spotlight socio-economic disparities across regions, with a strong emphasis on statistics.

Seen as the most complete document on Guatemalan society after the civil war, the report

has become a crucial source of information for NGOs, universities and the international

community. And it has led Guatemala’s government and civil society to recognize that

the national system of statistics urgently needs strengthening—not only to support

technical studies, but also to inform citizens as a requirement for democracy.

LATVIA AND LITHUANIA—NETWORKING ON HUMAN

DEVELOPMENT

Latvia and Lithuania have published national human development reports every year since

1995. The reports have covered the social effects of transition, human settlements, social

cohesion and poverty. Starting out by encouraging national debate on development

challenges, the reports have now inspired a cross-border academic network. Scholars from

three universities in each country are jointly developing a course curriculum to provide a

multidisciplinary overview of human development and its relevance to Latvia and

Lithuania. The reports will be part of the course curriculum.

CAMBODIA—HIGHLIGHTING GENDER DISCRIMINATION

Published annually since 1997, Cambodia’s human development reports

have provided a unique overview of human development in a country where scarcity of

reliable statistical data has been a major obstacle in developing sustainable social and

economic policies. The 1998 report drew public attention to the persistent discrimination

against women in access to education and health care. This message was reinforced by a

television documentary and four short spots on women in different occupations, broadcast

by all five national television stations. The reports have received an enthusiastic

response, and several NGOs and provincial government units are using them to train field

staff and community workers. Encouraged by this reception, UNDP and the Cambodian

government recently began transferring ownership of the report fully into Cambodian hands.

The initiative, with the participation of many NGOs, seeks to strengthen local

capacity in compiling and analysing data on human development.

_________________________________________________________________________ We, the

people of the Earth, are one large family. The new epoch offers new challenges

and new global problems, such as environmental catastrophes, exhaustion of resources,

bloody conflicts and poverty. Every time I see children begging in the street, my heart

is broken—it is our challenge and our shame that we are still unable to help those

who are vulnerable—children in the first place. Whatever are the problems or

perspectives for the future—the human dimension is what should be applied as the

measure of all events, towards the implications of every political decision to be made.

That is why the idea of human development promoted by UNDP is so important for us. I would

like to thank UNDP for bringing to life both the important concept of human development,

and these Reports. EDUARD SHEVARDNADZE, PRESIDENT, GEORGIA

_________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________

ASSESSING HUMAN DEVELOPMENT

The human development index (HDI), which the Human Development Report has made into

something of a flagship, has been rather successful in serving as an alternative measure

of development, supplementing GNP. Based as it is on three distinct

components—indicators of longevity, education and income per head—it is not

exclusively focused on economic opulence (as GNP is). Within the limits of these three

components, the HDI has served to broaden substantially the empirical attention that the

assessment of development processes receives.

However, the HDI, which is inescapably a crude

index, must not be seen as anything other than an introductory move in getting people

interested in the rich collection of information that is present in the Human Development

Report. Indeed, I must admit I did not initially see much merit in the HDI itself, which,

as it happens, I was privileged to help devise. At first I had expressed to Mahbub ul Haq,

the originator of the Human Development Report, considerable scepticism about trying to

focus on a crude index of this kind, attempting to catch in one simple number a complex

reality about human development and deprivation. In contrast to the coarse index of the

HDI, the rest of the Human Development Report contains an extensive collection of tables,

a wealth of information on a variety of

social, economic and political features that influence the nature and quality of human

life. Why give prominence, it was natural to ask, to a crude summary index that could not

begin to capture much of the rich information that makes the Human Development Report so

engaging and important?

This crudeness had not escaped Mahbub at all.

He did not resist the argument that the HDI could not be but a very limited indicator of

development. But after some initial hesitation, Mahbub persuaded himself that the

dominance of GNP (an overused and oversold index that he wanted to supplant) would not be

broken by any set of tables. People would look at them respectfully, he argued, but when

it came to using a summary measure of development, they would still go back to the

unadorned GNP, because it was crude but convenient. As I listened to Mahbub, I heard an

echo of T. S. Eliot’s poem “Burnt Norton”: “Human kind/Cannot bear

very much reality”.

“We need a measure”, Mahbub demanded,

“of the same level of vulgarity as GNP—just one number—but a measure that

is not as blind to social aspects of human lives as GNP is.” Mahbub hoped that not

only would the HDI be something of an improvement on—or at least a helpful supplement

to—GNP, but also that it would serve to broaden public interest in the other

variables that are plentifully analysed in the Human Development Report.

Mahbub got this exactly right, I have to admit,

and I am very glad that we did not manage to deflect him from seeking a crude measure. By

skilful use of the attracting power of the HDI, Mahbub got readers to take an involved

interest in the large class of systematic tables and detailed critical analyses presented

in the Human Development Report. The crude index spoke loud and clear and received

intelligent attention and through that vehicle the complex reality contained in the rest

of the Report also found an interested audience.

AMARTYA SEN, 1998 NOBEL LAUREATE IN ECONOMICS |